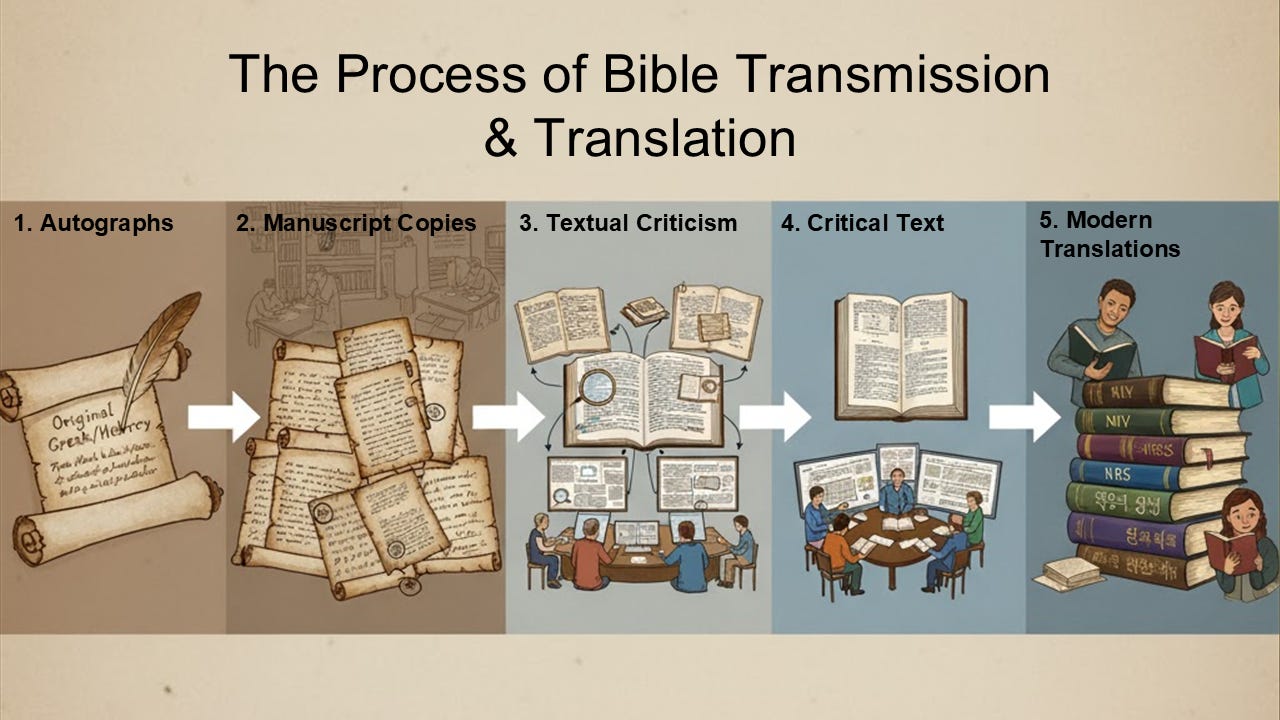

An Overview: From Original Inspiration to English

How do we get an English Bible?

Before we begin to dive into the topic of textual criticism we must know an essential truth: the Bible was not written in English. Every English Bible we have contains a translation from the original God-breathed Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek.

However, it is not quite that simple. Before we can translate the Bible from the original languages into English (or whatever our native tongue is) we must have a text to begin with. Now, at first glance that might seem easy, but it is not. Especially when it comes to the New Testament.

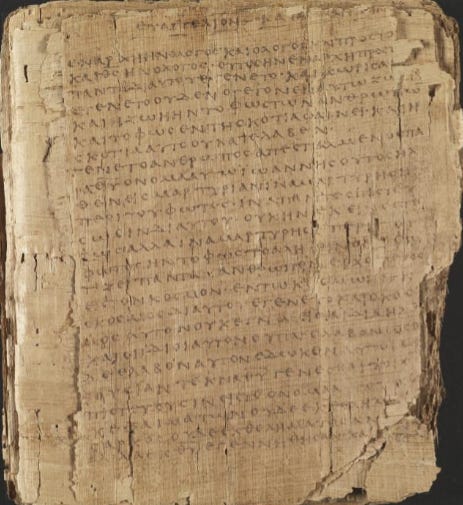

Currently, scholars have counted thousands of handwritten Greek manuscripts of the New Testament. Whether it be a manuscript of the Scripture itself, a quote found in the writings of the church fathers, or ancient church lectionaries, the New Testament has been preserved in a variety of ways in incredible fashion. In fact, every other ancient work pales in comparison when looking at the manuscript tradition.

With this in mind, we must acknowledge that God, in His grace, has chosen to preserve His Word, but He has likewise chosen to work through human vessels.

Humans are imperfect. We are not machines. We are not computers. Our bodies age and grow weak. We are merely “jars of clay” into which God has invested the incredible treasure of His gospel (see 2 Cor. 4:7).

As such, no two Greek manuscripts are completely identical. Instead, there are what is known as “variants” which are usually subtle differences that are attributed to copyist errors, because again, God chose to preserve His Word through imperfect human beings.

The oldest Greek manuscripts were written in a style that used only capital letters and no spaces or punctuation between letters or words. It is one continuous stream of letters that is then simply continued on the next line—sometimes even a word is broken up over two separate lines!

Now, take this difficult practice, combine the fact that it was handwritten, and expect people to copy without fail indefinitely for all time! Variants will inevitably come about because human beings are imperfect.

Now, this is no reason to panic! No Christian doctrine is affected by these variant readings.

There is no doubt that Jesus Christ came into the world as God-incarnate, was born of the virgin Mary, lived a perfect and sinless life, died as an atoning sacrifice for sins, was resurrected on the third day, ascended to heaven, promised salvation by a gift of grace received through faith, and that He is coming back again one day.

The fundamentals of the Christian faith are not impacted in the slightest. So, we can rest assured that what we believe is true to what the Scripture says as a whole no matter which manuscript we might be looking at.

Most of the time, variants are the result of little things, such as a repeated letter or some other mistake of the eyes jumping from one line to another.

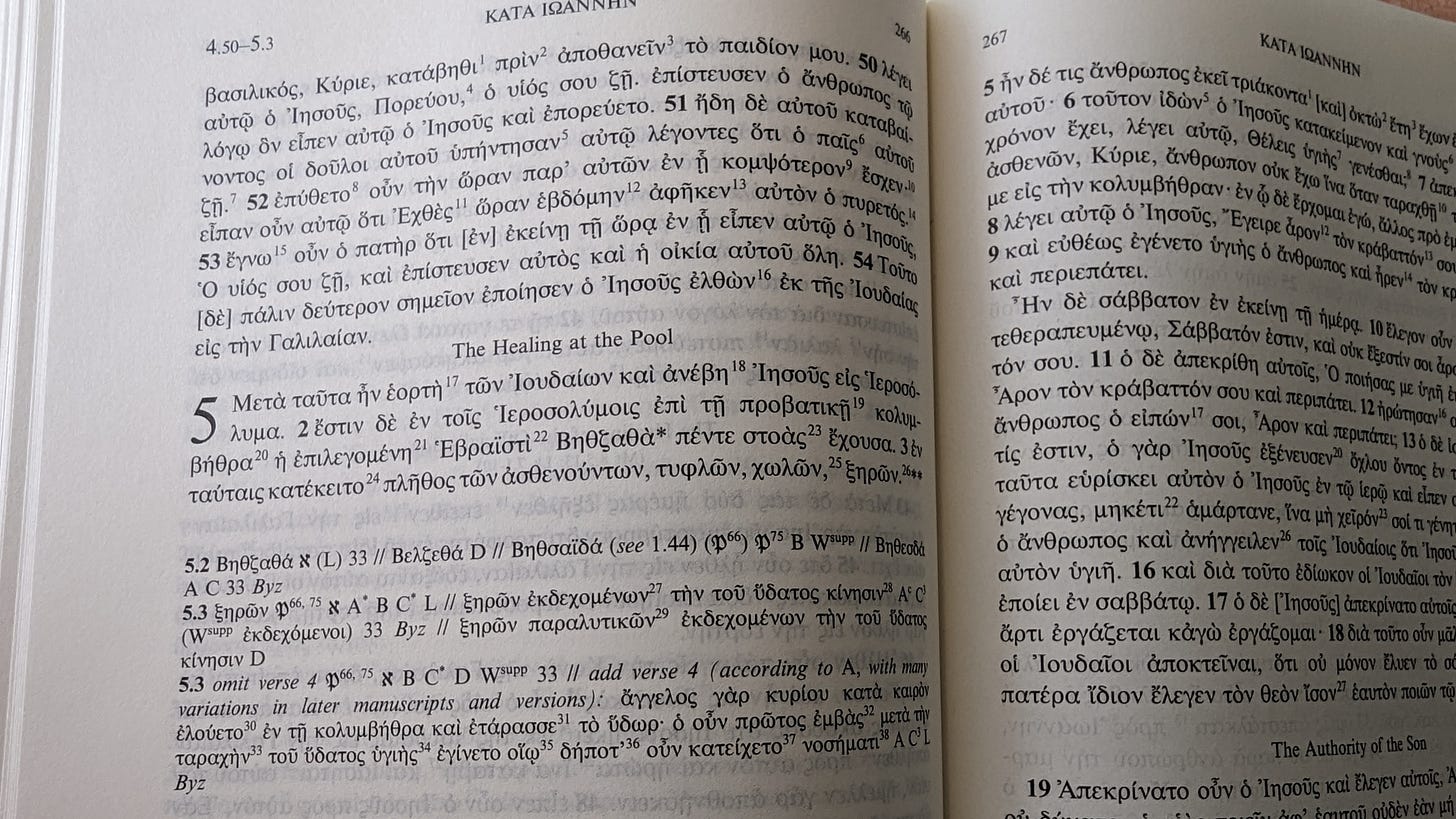

With this, sometimes entire verses come into question. Beyond eye-jumping, a verse might have found its way into a manuscript at one point because originally it was written as a comment in the margins of a manuscript almost like a footnote (see John 5:4; 1 John 5:7).

Other times, a scribe might have noticed that Matthew’s account of something missed a verse that Luke’s included and likely the scribe assumed that it belonged in Matthew’s account when truth be told it was just a different account!

There are a handful of verses that come into question in comparison to the breadth of the whole New Testament, and only two times when whole pericopes (sections) come into question (Mark 16; John 8).

Again, no Christian doctrine is impacted by these variant readings. Don’t worry, even in the shorter ending of Mark’s Gospel, Jesus is still raised from the dead, and the tomb is still empty!

However, these variant readings do exist whether we like it or not. So, when manuscripts differ, what do you do?

Overviewing Textual Criticism

Here is where textual criticism comes into play.

Now, at first glance, this sounds like a bad thing. If you are a conservative Christian and hear the word “criticism” you might assume that this some form of liberal practice that is intended to undermine the authority or accuracy of God’s Word. However, rest assured this is not the case.

Textual criticism is merely the process whereby scholars sift through the thousands of Greek manuscripts that we have available, acknowledging their differences, and determining to the best of their ability what the original writings or “autographs” would have said. Scholars Anderson & Widder define it simply in these terms:

“Textual criticism involves analyzing the manuscript evidence in order to determine the oldest form of the text.”[1]

With the great variety of manuscripts that we have today it is in fact a necessary thing.

Entire books are written on the topic of textual criticism. My overview here is far from exhaustive. There are complicated processes whereby certain readings are chosen instead of others. They look at both external evidence, that is which manuscripts are older and thereby closer to the originals. They also consider internal evidence. For example, “What seems to be most consistent with Paul’s theology, or writing style, found in his other letters?”

In weighing the options, they make choices based upon the likelihood of the different readings, and in modern translations you will often see footnotes for the other options.

From Critical Text to English

After scholars complete their work of textual criticism, they put together what is commonly called a “critical text.” This is the culmination of their work. In the case of the New Testament, the most commonly used Greek New Testaments today are the Nestle-Aland now in its 28th edition, and also the United Bible Society’s Greek New Testament now in its fifth edition.

With a critical edition in place, there is now a readiness to jump from the original language to our language. Each and every translation of the Bible will ultimately be a translation from the original languages, even if they use another edition as the starting place.

You might hear some argue against the Christian faith that, “The Bible has been translated so many times, you can’t trust it!” This claim is misguided.

The New Testament did not go from Wycliffe’s version to Tyndale’s, to the King James Version, to the American Standard Version, to the New International Version, to the English Standard Version to the Christian Standard Bible.

It is not as if modern translations are merely reworking former translations—they likewise go back to the original language that is found underlying those English translations. Hence, they are called translations. You do not need to translate English into English.

The English Standard Version (ESV) of the Bible is my preferred translation, and they offer this insight in the preface:

“To this end each word and phrase in the ESV has been carefully weighed against the original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, to ensure the fullest accuracy and clarity and to avoid under-translating or overlooking any nuance of the original text. The words and phrases themselves grow out of the Tyndale–King James legacy, and most recently out of the RSV, with the 1971 RSV text providing the starting point for our work.”[2]

It is clear they did not feel the need to start from scratch completely, as if older translations of the Bible were suddenly untrustworthy and needing to be thrown out. However, it is equally clear that their approach involved rigorous study and translation of the ancient texts themselves, and not merely English alone.

Likewise, you can find in the preface a specific note as to which critical editions they translated from. Again, in the case of the ESV:

“The ESV is based on the Masoretic text of the Hebrew Bible as found in Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (5th ed., 1997), and on the Greek text in the 2014 editions of the Greek New Testament (5th corrected ed.), published by the United Bible Societies (UBS), and Novum Testamentum Graece (28th ed., 2012), edited by Nestle and Aland.”[3]

A Note on the KJV-Only Debate

Now, I mentioned earlier about textual variants that are at times more significant in length. Sometimes there are entire verses that are not consistent in one version or another.

Perhaps you have heard about modern translations “removing” verses from the Bible in response to this. I have even heard it presented conspiratorially, as if, for instance, the NIV translators do not believe in the blood or the deity of Jesus! Every so often they just sneak a few more verses out to erode the foundations of the Christian faith. Give them just a few more years and historic Christian doctrines will be entirely absent from their demon-inspired work!

Frankly, this is just silly at its best, and slanderous at its worst (which is sinful I would remind us). I once took a class on “King James Version Appreciation” that came from a more critical background. One time we were tasked with overviewing a “missing” verse of our choice and we were then expected to present why it was a good verse and why it should be there.

Now, in this class, manuscripts never entered the discussion at all. In fact, the teacher probably had never even heard of textual criticism. I will not fault people who do not know any better in order to vilify them, but our question when looking at the textual tradition should never be: Is this good? Rather, the question should be: Is this original?

There are a lot of nice things that could be written, but was this written by the original divinely inspired author? That is what the textual critic is seeking to answer, and again they are not trying to hide things or erode at the foundation of the Christian faith. For one, the variant readings and omitted verses are found in the footnotes.

A Brief History

The King James Version uses a version of the Textus Receptus as its Greek New Testament. The original compiler, or textual critic was named Desiderius Erasmus. When Erasmus compiled his Greek New Testament, for the Gospels he had a grand total of two manuscripts from the twelfth century to reference.[4] Since then, two codices have been discovered, containing all four Gospels, that date to around the year 350 A.D.![5]

This moves the manuscript testimony back nearly one thousand years earlier, and yet even with this there are not significant changes. Out of the two longer sections in debate and 11 individual verses in question, Erasmus, with his limited resources, knew that there were questions. In fact, in his first manuscript the long ending of Mark was noted to be uncertain and the portion from John 8 was actually omitted![6]

Scholar, Peter Williams concludes,

“With just a fraction of the information we now have, and with only late manuscripts, Erasmus knew about the most significant textual questions in the Gospels.”[7]

In the last two hundred years many more manuscripts have been found, and older ones at that. Although it seems backwards, newer translations since the KJV actually operate off older and slightly more reliable manuscripts, only because that is when these discoveries have taken place.

A Defense

Some people are concerned that God has seemingly preserved a less-than version of His Word that would then be eclipsed by modern textual criticism and its finding of additional manuscripts.

Again, let it be noted though, that these older manuscripts have continued in the vast majority of places to validate that which we already knew. If anything, this gives even greater credibility to God’s Word! As such, they are a testament to the fact that God did indeed preserve His Word—He merely chose to do so through imperfect human beings, simple jars of clay that at times err in subtle ways. It is likewise a testament to the fact that no one ever systematically succeeded in controlling the manuscript record and only getting their version out there, which is a good thing.

Some have issue with the fact that older manuscripts were discovered at a later date and choose to continue to use the KJV or NKJV that hold to the Greek New Testament that originated as the Textus Receptus.

I will not fault people for using the KJV or NKJV if that is their preference. For some its theological, believing that God must have preserved His Word more perfectly and that it is only found in the King James. However, there are those who will say things like, “If it ain’t King James, it ain’t Bible!” or “I can use the King James to correct the Greek!”

These things are frankly silly to say and honestly are the opposite of what the original translators themselves would have wanted!

The very opening of their preface states:

“Zeal to promote the common good, whether it be by devising any thing our selves, or revising that which hath been laboured by others, deserveth certainly much respect and esteem, but yet findeth but cold entertainment in the world. It is welcomed with suspicion instead of love, and with emulation instead of thanks…”

In essence, they believed that aiming to do the right thing will oftentimes be poorly received. In context, they are certain they will get some flak for their translational work, but they found it to be something worthy of respect and esteem. It seems this would be their opinion of modern translations that have sought to build upon their own work in bringing God’s Word into the common vernacular of today’s Christian.

Further, under the heading “The Translation of the Seventy” found within the preface, the translators point out:

“no cause therefore why the word translated should be denied to be the word, or forbidden to be current, notwithstanding that some imperfections and blemishes may be noted in the setting forth of it.”

They implicitly therefore deny the perfection even of their own translation. Translations will never be perfect because no two languages line up perfectly, the ESV translators echo this in their preface as well.

Even more, the KJV translators under the same heading as the former quote, point out:

“...we do not deny, nay we affirm and avow, that the very meanest translation of the Bible in English... containeth the word of God, nay, is the word of God.”

Clearly, they would not have held that their translation was the only inspired version of the Bible, for they concluded that even the least refined translations still are the Word of God!

There are many more points to make here but let us simply conclude that the translators would not have been a part of a King James-Only movement that would slander and ridicule other translators and their efforts to bring God’s Word into the language of the everyday people.

God did not inspire the King James Bible any more than He inspired the English Standard Version or the New International Version (NIV) which I have heard jokingly alluded to as the “Not Inspired Version.”

If this is our understanding of inspiration, then we ought to toss out every English Bible because they are all equally uninspired!

Not only this, if the KJV was our only hope then all Spanish speakers would be forced to learn English in order to read God’s Word, does that not seem backwards? This would then be the same for the hundreds of other languages found on the planet!

Truth-be-told, God inspired His servants to write in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Koine Greek.

Now, this does not mean that I believe that the English is automatically therefore uninspired and is no longer profitable (see 2 Tim. 3:16-17). I hope it merely shows the point that those who hold to the position that the KJV is inspired to the neglect of the others is really an intellectually foolish position to hold.

Concluding Thoughts

In seminary, I was taught Greek and Hebrew at an elementary level. I can read very few things in Hebrew; it is incredibly difficult. However, I can read Greek decently. I am steadily trudging through my Greek New Testament every morning and spend time in the original Greek every time I am studying a New Testament passage to preach. I still have a long way to go before I am great at it, and I still have a ton of vocabulary to learn. I am hoping once I have made sufficient and lasting progress in Greek to then dive back into Hebrew and to hopefully grow there.

The study of the original languages is a great blessing that has been fun for me. From everything I know and from everyone I have talked to, I have found our English Bibles do a great job at conveying God’s Word to us in our own language. Learning other languages, especially ancient ones, is not easy. I remember leaving my Greek II residency at Lancaster Bible College thinking my head would explode (literally I had an incredibly uncomfortable burning sensation in my head for over an hour afterwards, participles are not an easy thing to learn, especially cramming them all into one week!).

I have progressed a lot since then, but I am still far from a scholar. It is a laborious process, and that part of the equation only comes into play after others have taken countless hours sifting through manuscripts to bring us the critical edition that I sit down to read.

A critical edition, mind you, that is as close to the autographs as we can possibly devise and is certainly reliable. Scholar, Craig Blomberg, agreeing with New Testament scholar Dan Wallace states,

“we can say with a high degree of confidence that we have the actual text of the autographs of the New Testament books in our modern critical editions of the Greek New Testaments.”[8]

Likewise, he further concludes,

“The sheer quantity of manuscripts we have gives us a greater level of confidence in reconstructing the original autographs of the New Testament than for any other books in existence from the ancient Near East or Mediterranean World.”[9]

As I conclude this survey, I hope that you are stirred with the immense privilege of having a copy of God’s Word in your own language, and in your vernacular.

I think to the words of William Tyndale who once said to a priest,

“If God spare my life, ere many years, I will cause a boy who drives a plough to know more of the scriptures than you do.”

The efforts of various saints throughout the centuries to copy manuscripts, to compile them, and to finally translate them should have us eternally grateful.

So, let us not slander those who disagree with us on these issues, and certainly let us not slander those who have given their lives to this work because of misunderstanding. We are all part of the same Kingdom, serving the same Lord, against a common enemy.

As we look to the immense task that it took to bring it to us today, we should respond with dedication to the much simpler task of reading and studying it ourselves in a translation we can understand. Finally, we should strive to complete our Bible study with application knowing that we ought to be doers of the Word and not hearers only (Jas. 1:22).

I hope this short introduction to the concept of textual criticism proved helpful to your understanding of how we got our English Bibles. It is not even remotely close to a comprehensive treatment of the topic, but I hope this puts the topic on the bottom shelf for you enough that you have a greater understanding than you did before.

[1] Amy Anderson & Wendy Widder, Textual Criticism of the Bible. (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2018), 6.

[2] The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2016).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Peter J. Williams, Can We Trust the Gospels? (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2018), 112-113.

[5] Ibid., 113.

[6] Ibid., 114.

[7] Ibid., 116.

[8] Craig Blomberg, The Historical Reliability of the New Testament: Countering the Challenges to Evangelical Christian Beliefs. (B&H Academic, Nashville: TN), 623.

[9] Ibid., 644.

This was an excellent and engaging overview of a complex and extremely important discipline.